Higher PFAS levels in Arctic precipitation during sunlight

William Hartz returned to the same glacier ten times during his stay on Svalbard.

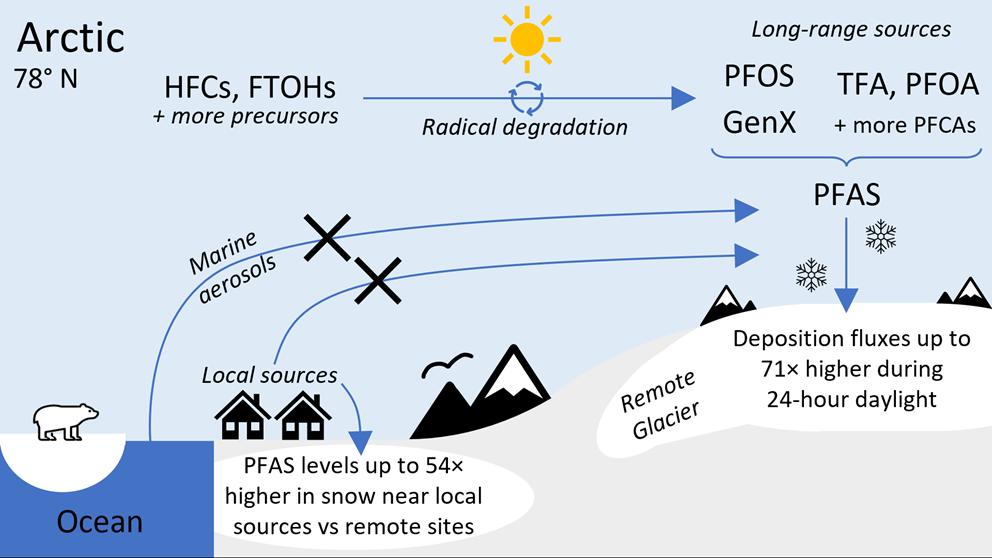

Snow falling on Svalbard contains higher levels of PFAS during the sunny months compared to the dark winter months. Research from Örebro University shows up to 71 times higher levels of these chemicals during the archipelago’s sunniest period.

“Sunlight triggers chemical reactions in the atmosphere transforming and carrying PFAS into the snow during the Arctic summer”, says chemist William Hartz.

The article Sources and Seasonal Variations of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Surface Snow in the Arctic is published in Environmental Science and Technology[JG1] . The study results from collaboration between Örebro University, Oxford University, The University Centre in Svalbard, and NILU, a Norwegian climate and environmental research institute.

PFAS refers collectively to the thousands of man-made chemicals that take a very long time to break down in nature. None of these substances occur naturally – also called forever chemicals, and several are suspected of negatively affecting humans and nature. These chemicals, used in clothing, kitchenware, and waterproofing agents, are spread throughout nature and in the bodies of animals and humans worldwide. For example, a type of PFAS called PFOS has been found in the blood of polar bears.

“Similar PFOS levels have been measured in polar bears as in humans living near PFAS factories in China. It’s astounding that polar bears in such remote locations carry the same PFOS levels as people in the world’s most polluted areas,” says William Hartz, a postdoctoral researcher at Örebro University.

In collaboration with other researchers, he has published data from a study initiated in 2019 when he lived on Svalbard from January to August. Svalbard is an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, and the town of Longyearbyen is one of the world’s northernmost inhabited places.

“We know from lab experiments that sunlight can transform PFAS in the atmosphere into other types of PFAS, and I wanted to investigate how this occurs in a remote location,” explains William Hartz.

He selected a glacier he visited ten times during his eight months on the island. Nature’s forces decided how he travelled – whether by snowmobile, skis, or foot – as well as when sampling could occur. He monitored weather forecasts closely to avoid heading out during strong winds or high avalanche risk.

“I collected between 10 and 20 kilos of snow each visit. All in all, about 100 kilos of melted snow was transported from Longyearbyen Airport to Sweden.”

Back in the lab at Örebro University, William Hartz and his colleagues found PFAS concentrations in the snow up to 71 times higher for trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) during sunshine periods, when the sun shines around the clock, compared to the darkest months when the sun never rises.

“Despite awareness of the chemical processes, the team was surprised by the extreme seasonal difference in PFAS levels”, says William Hartz.

TFA is one of the so-called ultra-short PFAS substances comprising one to three carbon atoms. Researchers have also found 13 to 22 times higher levels of PFOA and PFOS in snow falling during summer compared to winter. PFOA and PFOS were manufactured in large volumes in the 1950s and used in products like Teflon and fire extinguisher foam. While these substances are still used in various industries, they are banned in the EU.

Sunlight initiates photochemical reactions, causing PFAS in the atmosphere to transform into other types of PFAS. These atmospheric PFAS originate primarily from factories and waste management and can travel thousands of miles before falling as rain or snow.

“This could explain why a previous study found the chemical GenX on the Arctic Ocean’s surface. Since production of GenX began in 2009, not enough time has passed for it to reach the Arctic Ocean even if it were dumped into the North Sea. Still, we measured 41 times higher GenX levels after the sun shined, suggesting its presence in the Arctic might be due to atmospheric processes.”

William Hartz sees the research as an essential piece of the puzzle for understanding PFAS spread around the globe. Despite the seemingly grim results, William Hartz remains cautiously optimistic about the future:

“If we can stop emissions of certain substances, we could potentially see lower PFAS levels in rain and snow within just a few years."

Text: Mikael Åberg

Photo: Private

Translation: Jerry Gray