Microplastics in seas absorb lower levels of environmental toxins than researchers feared

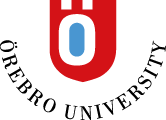

Plastic microbeads like these were studied. These are found in some cosmetics but are also used as a raw material in manufacturing plastic products.

The risk that microplastics will absorb and transport environmental toxins in seas and lakes is lower than previously feared. According to a new doctoral thesis, microplastics which are just a few millimetres thick, do not transport toxic substances in seas and lakes as well as researchers once believed.

“I don’t think you should be concerned about eating fish,” says Christine Schönlau, a plastic researcher at Örebro University.

Even though many environmental toxins are banned today, they still lie at the bottom of our seas and lakes. Researchers have been concerned that microplastics could absorb various pollutants and spread them further. Toxins are found in the bottom sediment of our waters, where it takes a very long time to break them down.

“These toxins don't dissolve in water, because they don’t like water. They want to stick to something else,” says Christine Schönlau.

It is a well-known problem that animals ingest plastic. Since the spread of small plastic particles in the oceans was discovered in the 1970s, plastic has been found in the stomach contents of some 180 animal species.

One fear among researchers has therefore been that toxins could adhere to small plastic particles. This could mean that they are transported further into seas and the ecosystem, for example, by being swallowed by fish.

Studying microplastics in seas

Christine Schönlau at Örebro University has now investigated the matter. In her study, she placed newly produced microbeads that are two to four millimetres into different seas and freshwater lakes, to determine if pollutants are transported with the plastic. The study looked at six different types of plastic.

To test the plastics microbeads in a range of environments, they were placed in different parts of the world. The waters included in the study are Fiskebäckskil on the Swedish west coast, Askö on the Swedish east coast, the Great Barrier Reef in Australia and San Diego’s polluted harbour in the USA. Samples were also taken from a Swedish freshwater lake, outside of Kumla.

The results presented in her doctoral thesis are thus far reassuring. Christine Schönlau’s investigation shows low concentrations of the environmental pollutants’ dioxin, PCB and chlorinated pesticides like DDT. The conclusion is that the risks of exposing the ecosystems in seas and lakes to these types of chemicals via plastics are not a high as previously suspected.

“I don’t think you should be concerned about eating fish. The fish have already been exposed to chemicals. If they were to eat some plastics, it will probably not change the concentration of such pollutants in the tissue of the fish.”

Surprisingly low levels in the Baltic Sea

On the other hand, plastic in our seas leads to many other problems. Therefore, it is also good news that the amount of microplastics measured in the surface water of the Baltic Sea is low.

To determine the concentration of microplastics in various places, researchers pumped up surface water, trawling it with special equipment to trap the small particles. Despite there being many larger cities around the Baltic Sea, the number of particles in the surface water was low. Measurements showed 0.04 plastic particles per cubic meter of water on average.

“It was quite unexpected to find such low concentrations of microplastics in the Baltic Sea,” says Christine Schönlau.

Further research is necessary to determine if the smallest plastic particles – less than two millimetres – respond in the same way to environmental toxins, as the somewhat larger particles did. At present, there are particular technical difficulties in examining such small microplastics, which may be just one plastic fibre.

“It’s important that this research continues. It is also vital to stop the pollution of our waters with plastics,” concludes Christine Schönlau.

Link to doctoral thesis: Microplastics in the Marine Enviroment and the Asessment of Potential Adverse Effects of Associated Chemicals

Text and photo: Jesper Mattsson

Photo: Christine Schönlau

Translation: Jerry Gray

Microplastics:

Microplastics are small plastic particles, up to five millimetres thick.

Many times, these are parts of various plastic objects that have disintegrated, but may also include plastic manufactured as small particles.

Microplastics are found today even in places seldom visited by humans, like the Arctic zone.

Research has shown that plastic in the seas can be deadly for many animal species, for example, when the animals ingest plastic.

Testing was performed in:

San Diego, USA

Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef, Australia

Fiskebäckskil, Sweden

Askö, Sweden

Söderhavet, Kumla, Sweden